Sitting here with Akiko, trying to explain Burning Man, I realize it's impossible.

It's like trying to explain color to someone who's been blind their whole life. Or trying to describe music using only mathematics. The description might be accurate, but it misses the essence.

But I'll try anyway.

Because Burning Man was proof. Proof that everything I'd experienced on the journey—the flow states, the synchronicities, the sense that another world was possible—wasn't just travel euphoria or psychedelic delusion.

It was real.

And thirty-five thousand people were creating it together in the Nevada desert for one week every year.

I went in late August 2002, about a month after getting back to New York.

The timing was perfect—or maybe it was just another synchronicity. I'd been back from the journey for a few weeks, trying to figure out what to do next, when I ran into an old friend from the trance scene.

"You going to Burning Man?" he asked.

"I don't know. What is it?"

He laughed. "You went to India and didn't hear about Burning Man? Dude, it's like if all the full moon parties in Goa happened in one place for a week. You have to go."

So I went.

Drove across the country with three people I barely knew. Thirty hours straight through Middle America, watching the landscape flatten and empty until we were in desert, then more desert, then finally—rising out of the heat shimmer like a mirage—the city.

Black Rock City.

Population: 35,000.

Lifespan: One week.

The first thing that hits you when you arrive at Burning Man is the dust.

The playa—the dry lakebed where the event happens—is covered in this fine alkaline powder. It gets everywhere. In your nose, your eyes, your hair, your clothes. It coats everything like moon dust.

The second thing that hits you is the heat. This isn't pleasant desert warmth. This is biblical, apocalyptic heat. The kind that makes you understand why people hallucinate in deserts. Why prophets went into wilderness and came back with visions.

And the third thing—the thing that makes you forget about the dust and the heat and every other physical discomfort—is what they've built.

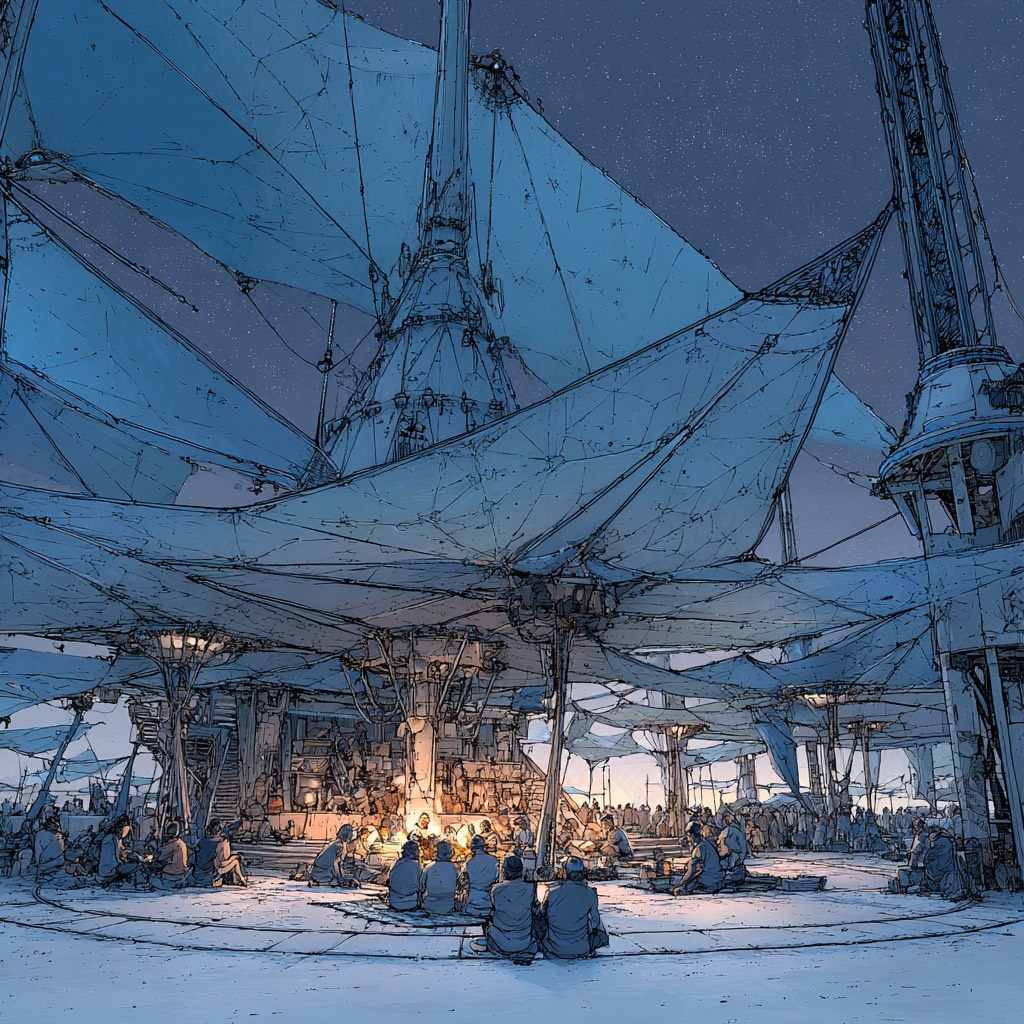

Imagine if someone gave artists a blank canvas the size of several square miles and unlimited creative freedom. No rules except: make something amazing, and leave no trace when you're done.

That's Burning Man.

Art everywhere. Not gallery art. Not museum art. Art you can climb on, walk through, burn down. A forty-foot wooden temple. A fire-breathing mechanical whale. A full-scale pirate ship manned by people in elaborate costumes, sailing across the desert. Geodesic domes covered in LED lights. Sculptures that look like they're from another planet.

And in the center of everything: the Man. A wooden effigy fifty feet tall, standing on a platform, arms raised to the sky. On the last night of the festival, they burn him. Thirty-five thousand people gather in a circle and watch him go up in flames.

But that's the end. Let me tell you about the beginning.

My first night, I was wandering through the city—and it is a city, with streets laid out in a mandala pattern, different neighborhoods, different energy in each zone—when I heard music.

Trance music.

I followed the sound to a camp that had set up a full outdoor sound system. Not a DJ booth—a proper system, the kind you'd find at a festival. And the camp was giving away chai. Free chai. As much as you wanted.

"Gift economy," someone explained when I asked why they weren't charging. "That's how Burning Man works. No money. You can't buy anything except ice. Everything else is gifted."

I stood there, chai in hand, listening to trance echo across the desert, and felt something I hadn't felt since leaving India.

Home.

Not home like my parents' apartment in New York. Home like: this is my tribe. These are my people. This is the world I've been trying to find.

Sitting here with Akiko, I'm trying to convey the feeling of those seven days.

Every morning I'd wake up in my tent—which felt like a sauna by 8 AM because of the heat—and emerge into a city that looked like someone's fever dream.

Art cars—vehicles converted into rolling sculptures—would cruise past. A glowing octopus. A giant high-heeled shoe. A double-decker bus transformed into a moving disco. Each one blasting different music, offering different experiences.

People in costumes. Not Halloween costumes—costume as art, as identity exploration, as play. Steampunk pirates. Robot mermaids. Victorian vampires. Naked except for body paint. Or wearing nothing but a tutu and a smile.

And everywhere: gifting.

Someone would hand you a popsicle in the middle of the day. Someone else would offer to braid your hair. A camp would serve you a gourmet meal for free. Another would give you a foot massage.

The only currency was participation. Contribution. Showing up authentically and offering whatever you had to give.

It was everything I'd been trying to articulate about the gift economy I'd experienced traveling. About how when you remove money from transactions, human beings naturally want to give. To create. To share.

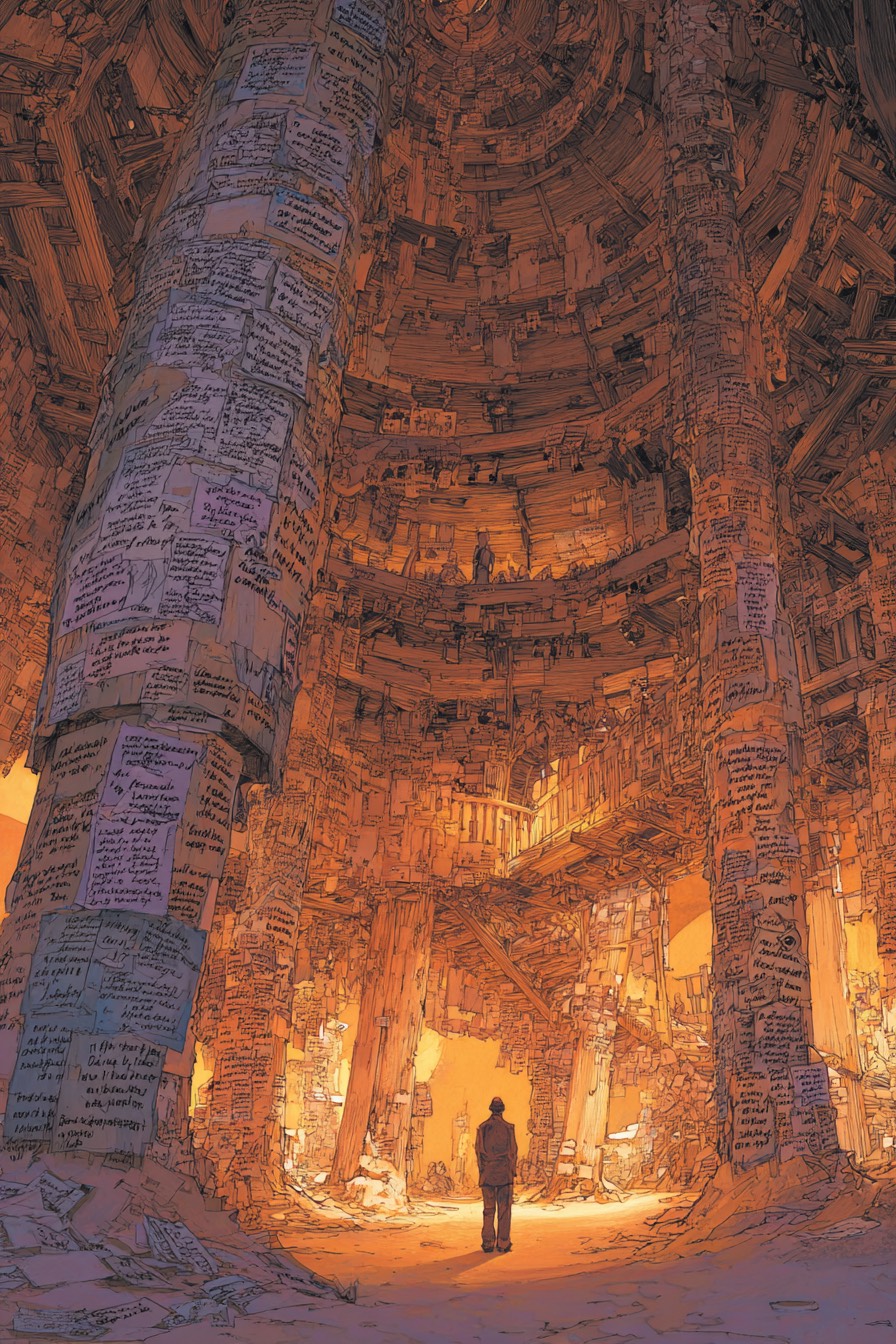

One afternoon, I wandered into the Temple.

The Temple was different from the Man. Quieter. More sacred. Built as a space for grief and remembrance. People would write messages on the wooden walls: names of people who'd died, confessions, prayers, things they needed to let go of.

I stood there reading them. Thousands of messages. Layers and layers of human pain and loss and hope and love.

And I thought: This is real community. This is what happens when you create space for people to be vulnerable. To grieve together. To acknowledge the weight they're carrying.

On the last night of the festival—after they'd burned the Man in a massive fire ritual that drew the entire city into a circle—they burned the Temple.

It wasn't a party. It was ceremony. Thirty-five thousand people standing in silence, watching this beautiful structure go up in flames, carrying with it all the grief and prayers and confessions people had written on its walls.

I cried. I wasn't alone. Half the crowd was crying.

Because it was beautiful. And heartbreaking. And profound.

A collective letting go.

But Burning Man wasn't all deep spiritual moments. It was also gloriously, ridiculously hedonistic.

One night I ended up on an art car—a converted school bus covered in lights and lasers—with a hundred people dancing on top of it as it crawled across the playa at three miles an hour.

The DJ was playing psychedelic trance. The same music I'd heard in Goa, in Tulum, in Guatemala. But here it felt different. More integrated. Like it was the soundtrack to something larger than a party.

We danced for hours. As the sun came up, someone started passing around a joint. Then someone else had mushrooms. Then someone had a bottle of tequila.

And normally—in the default world—that would be sketchy. Strangers sharing drugs and alcohol would feel dangerous or irresponsible.

But here it felt natural. Because the entire ethos of Burning Man was: we're all responsible for ourselves. We're all adults. We're all here to explore and play and push boundaries. And we trust each other to do it consciously.

Radical self-reliance. Radical self-expression. Radical inclusion.

Those were the principles.

And they worked.

Sitting here trying to explain this to Akiko, I keep coming back to one word: temporary.

Burning Man is a temporary city. A temporary utopia. A proof-of-concept that lasts exactly one week before everyone packs up and goes back to their regular lives.

And that temporariness is crucial. It's not trying to be a permanent alternative society. It's not trying to replace the default world. It's creating a space where people can experience what's possible. Where they can try on different identities, different ways of being, different social structures.

And then they take that back with them.

That's the whole point.

You come to Burning Man, you see what a gift economy looks like in practice, and maybe—just maybe—you start thinking about how you could implement gifting in your regular life.

You experience radical self-expression, and maybe you get a little braver about being yourself in the default world.

You participate in community art projects, and maybe you realize you don't need permission or funding or credentials to create something beautiful.

Burning Man is a seed. You plant it in the desert for one week, and then people carry those seeds home and plant them wherever they live.

On the last day, they have a ceremony called "leave no trace."

Thirty-five thousand people spend hours combing the playa, picking up every piece of trash, every scrap of debris. The goal is to return the desert to exactly how it was before they arrived.

No permanent structures. No lasting impact. Just the temporary magic of a city that existed for one week and then vanished.

I spent my last morning on my hands and knees, picking up tiny pieces of glitter and cigarette butts, thinking about this.

About how the beauty was in the impermanence. How creating something amazing and then letting it go was more powerful than trying to make it last forever.

About how that was true for Burning Man, but also true for everything. For relationships. For moments. For life itself.

You create beauty. You participate fully. And then you let it go.

Driving home across America—exhausted, sunburned, covered in dust—I felt different.

The journey through Central and South America had shown me that alternative ways of living were possible. That communities existed outside the Matrix. That synchronicity was real and the universe responded to intention.

But Burning Man showed me something else.

It showed me that you didn't have to leave America to find the alternative. You didn't have to go to India or Peru or remote beaches in Mexico.

The alternative was here. Being created by people just like me. People who'd grown up in the default world and decided to build something different, even if only temporarily.

Thirty-five thousand people coming together to say: "We know another world is possible. And we're going to prove it. For one week, we're going to live like money doesn't matter, like creativity is the highest value, like community is real, like we can trust each other."

And it worked.

Not perfectly. There were problems—of course there were problems. But it worked well enough to prove the concept.

Sitting here with Akiko, months after Burning Man, months after the journey, I'm starting to see the pattern.

The journey showed me what's possible.

Burning Man showed me that I wasn't alone in wanting it.

And now—here in New York, dictating this story, trying to make sense of it all—I'm realizing what comes next.

Teaching.

Not in a classroom. Not with credentials or authority. But teaching in the sense of: sharing what I've learned. Creating spaces where others can have their own experiences. Being the elder I needed when I was younger.

Michael at Solstice Grove did that for me. He showed me it was possible to live outside the system. To make art and build community and stay connected to consciousness.

And now it's my turn to do that for someone else.

The circuit continues.

The pattern repeats.

But each time it repeats, it evolves. Gets a little clearer. A little more refined.

That's what Burning Man taught me.

You don't have to build the permanent utopia. You just have to show people what's possible. Plant the seed. Let them take it home and see what grows.

Akiko stops typing, stretches.

"So you're saying Burning Man is like... a reset button for society?"

"Kind of," I say. "Or maybe more like a prototype. A working model of what could exist if we organized differently. If we valued creativity over productivity. If we trusted each other instead of fearing each other."

"But it only lasts a week."

"Yeah. But that's enough. Because once you've seen it—once you've lived in a city with no money, where people gift freely, where art is everywhere and everyone participates—you can't unsee it. It changes your baseline for what's possible."

"And then you go back to Babylon."

"And then you go back to Babylon," I agree. "But you're different. You carry the temple with you. The fire. The reminder that another world isn't just possible—it's already happening. You just have to know where to look."

Outside the window, New York is the opposite of Burning Man. Permanent structures. Money everywhere. People rushing, disconnected, trapped in routines.

But I know now—after the journey, after Burning Man, after these months of trying to integrate it all—that the same principles apply everywhere.

Gifting. Flow. Synchronicity. Community. Trust. Creativity.

They're not location-dependent. They're practice-dependent.

You can create Black Rock City anywhere. Even in Babylon. Even in your own apartment, your own neighborhood, your own life.

You just have to choose it.

Over and over.

In each moment.

That's the practice.

That's what I'm learning to do.

Akiko closes her laptop.

"Next session?" she asks.

"Next session."

She leaves. I sit in the quiet apartment, watching the sun set over Brooklyn.

In two weeks, we'll finish. The story will be told. All the pieces captured. And then I'll have to figure out what to do with it.

But for now, I'm here. Present. Practicing what I learned.

Showing up authentically. Trusting the process. Letting the pattern reveal itself.

The temporary city taught me: impermanence is not a problem. It's the whole point.

You create beauty. You share it. You let it go.

And then you do it again.

Forever.

That's the practice.

That's the path.

That's the dance.