Sitting here with Akiko in this Williamsburg apartment, trying to explain what happened in Tulum, I keep coming back to the same thing: some moments change everything.

You don't know it while you're living them. They feel like any other conversation, any other bus ride, any other day on the beach. But looking back now—six months later, sitting in this folding chair while Akiko types and rain streaks down the windows—I can see it clearly.

Tulum was where everything clicked. Where all the scattered pieces—the trance music, the internet, the Mayan prophecies, the feeling that we were living through something unprecedented—suddenly assembled into a pattern.

It started with a bus ride.

The bus was already at the station when I arrived, engine running, about to leave. I'd just said goodbye to Oliver in Cancun—one of those instant friendships you make on the road, the kind where you meet someone at 2 AM in a hostel and by dawn you're planning the next leg of your journey together. But Oliver was heading to Belize, and I was going south to Tulum.

I gave him one last hug and climbed aboard.

The bus was nearly empty. Three other passengers, scattered across the reclining seats. One of them caught my eye immediately—a British guy about my age, maybe a bit older, with messy hair pulled back in a ponytail and a fluorescent yellow t-shirt covered in Mayan hieroglyphics. He waved me over to the back of the bus with this huge grin.

"Nice to see you mate!" he said as I sat down, high-fiving me. "Wasn't sure you were going to make it."

His name was Tarquin.

And over the next few hours, on that bus ride from Cancun to Tulum, he basically rewired how I understood the world.

Tarquin was one of those people you meet traveling who feels like they've been doing this forever. Not tourists. Not even travelers really. Just... permanent nomads. People who've figured out how to exist in the gaps between countries, between identities, between the cracks of the system.

"I was born in Goa," he told me as the bus pulled out of Cancun. "1973. My parents were hippies. Pushed me out on a beach in Vagator. I literally grew up on the dance floor—my babysitters were the chai mamas who served tea on embroidered quilts at the edge of the parties."

I laughed. "So you've been in the scene your whole life."

"Born into it, mate. I like to tell people I'm from the future."

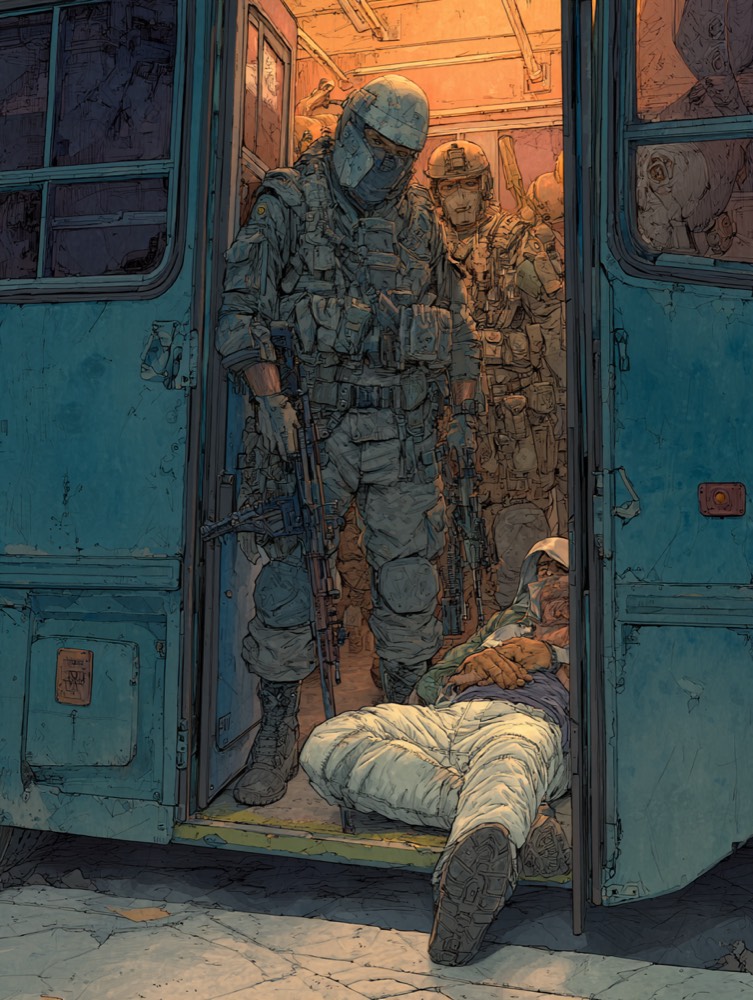

The sun was rising now, Cancun fading behind us on the horizon. Construction everywhere—they were building an elevated highway through the jungle, and every so often we'd hit a military checkpoint. Armed soldiers with Rottweilers, scanning passengers.

Tarquin had this trick where he'd fall asleep right before each checkpoint—just suddenly nod off, hood pulled over his face—and wake up the moment we cleared it. I'm not sure if it was intentional or some kind of traveler's sixth sense, but it worked every time.

"So what brings you to the Yucatan?" he asked, once we'd cleared another checkpoint.

"The Mayans," I said. "The 2012 prophecy. I studied philosophy in college and wrote my thesis on the evolution of consciousness. And it seemed like... I don't know, like everything's been speeding up lately. The internet, globalization, all of it. And then I heard that the Mayan calendar ends in 2012, right when things feel like they're accelerating faster than ever. Seemed like too much of a coincidence."

Tarquin's eyes lit up. "My parents were obsessed with the Mayans too. That's why they ended up in Central America after Goa. Following the pyramids."

We talked for hours. About trance music, about the hippie trail from Europe to India, about how the internet was creating a global village, about psychedelics and shamanism and the feeling that our generation was living through something unprecedented.

"You know what I think?" Tarquin said at one point. "I think you and I are part of a very special generation."

"What do you mean?"

"We grew up analog but came of age digital. Born between like 1975 and 1980. We played outside as kids, climbed trees, scraped our knees. But we also had Nintendo. We grew up with vinyl records and cassette tapes, but we also got our first email in college. We have one foot in each world."

He was right. I'd been thinking about this too, but I'd never heard anyone else articulate it.

"It's like," I said, "we're the first generation of the global village. When I was a kid in Greece, we had two TV channels. Both government-run. They'd start at noon with the national anthem and the Greek flag being raised, and end at midnight the same way. Everything looked old, faded, dusty."

"And then?"

"And then one day—I was thirteen—suddenly we had forty channels. MTV, CNN, Sky, channels from all over Europe. It was like someone flipped a switch. Within a few years, Greece transformed. Kids were wearing baggy pants and baseball caps backwards, listening to hip-hop, skateboarding. This new global youth culture just... rippled through."

Tarquin was nodding intensely. "Same thing happened everywhere. Goa, London, Cape Town, everywhere I've lived. The internet is connecting us. That's why we're sitting on this bus in Mexico having this conversation. You're Greek, grew up in Athens. I'm British, grew up in India. But we're from the same tribe."

The bus slowed. We'd arrived in Tulum town.

Tulum town was quiet at 9 AM. A few closed restaurants, some trucks kicking up dust on dirt roads, a couple of taxi drivers at the gas station.

"My friend recommended staying at the beach," Tarquin said. "There's a government-run camping site with beach bungalows."

"Sounds perfect."

We negotiated a ride and ten minutes later we were walking through mangroves onto the most magnificent white sand beach I'd ever seen. Endless fine coral powder, turquoise ocean on one side, vibrant green jungle on the other. Palm trees casting shadows, breaking up the blinding whiteness.

The only structure was an open-air restaurant with orange walls and a thatched palm-leaf roof. Sand floor, wood stove, the smell of eggs and beans cooking. A young Mayan woman sat at a table near the entrance, reading.

She looked up as we approached. "Welcome. Looking for a place to stay? I'm Itzel."

She showed us the bungalows—little circular huts scattered on the sand, thatched roofs, concrete walls about a meter high, wooden doors with padlocks. Inside each was just a bed with a thin mattress on the sandy floor.

"I'll take it!" I said immediately.

I dropped my bag, lay back on the bed, and for the first time on the trip I felt this overwhelming sense of freedom. Like my body was transparent, weightless. Like I was exactly where I was supposed to be.

"Pretty fucking sweet, right?" I yelled to Tarquin.

"You guys are crazy," Itzel said, smiling.

That afternoon, Tarquin and I sat at the edge of the ocean, watching waves break on the same horizon the Mayans had watched centuries before.

He pulled something from a hidden pouch in his crotch—a tiny ceramic chillum and a ball of black hash.

"Manali cream," he said. "All the way from Parvati Valley. I've been waiting to smoke this on the shores of the New World."

He prepared it carefully, mixing hash and tobacco, wrapping the end of the chillum with wet cloth from his sarong. The ritual felt ancient, intentional.

"Bom Bolenath," he chanted as he lit it.

I inhaled. The smoke was rich, earthy, tasting like mountains and gods. A warm calm spread through me.

"Tell me about those mysteries in ancient Greece you mentioned on the bus," Tarquin said.

"The Eleusinian Mysteries. They lasted over two thousand years. Everyone had to participate at least once—men, women, even slaves. But talking about what happened was punishable by death. That's why we know so little."

"Like the trance parties," Tarquin said. "You don't talk about what happens on the dance floor. It ruins the magic."

"Exactly. And that's the thing—I think we're reinventing these ancient rituals. Full moon parties in the jungle, people following fluorescent ribbons tied to trees to find the gathering. It's the same impulse. We need mystery. We need magic. The modern world is too disenchanted."

Tarquin exhaled a huge cloud of smoke. "Modern religion doesn't do it anymore. Nobody goes to church. We need experiences we can feel in our deepest selves."

"That's what I'm trying to document," I said. "I brought all these cameras, video equipment. I want to capture this moment. Show that there's something real happening, something beyond the corporate Matrix we're supposed to buy into."

We talked until the sun set, the conversation spiraling through territories I'd never explored with anyone before.

And then, as stars began to appear, Tarquin said something that stopped me cold.

"You know what the whole digital revolution is really about?"

"What?"

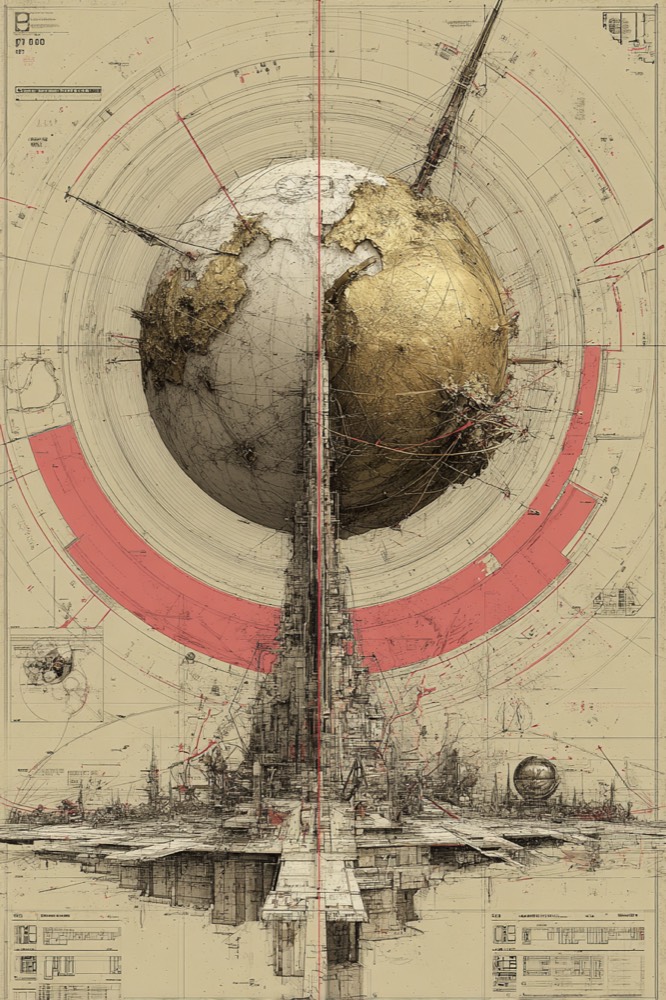

"It's about zero and one."

Sitting here with Akiko now, I'm trying to remember exactly how Tarquin explained it. Because what he said that night—what we figured out together as we sat on that beach, high on Himalayan hash and drunk on ideas—became the foundation for everything that came after.

Zero and one.

0 and 1.

Off and on.

Nothingness and somethingness.

Female and male.

Dionysian and Apollonian.

Intuition and reason.

The pendulum swinging back and forth through all of human history.

Tarquin started with the technology.

"Think about how a vinyl record works," he said. "Sound is a vibration in the air. The vibration hits a membrane, which moves a needle, which carves grooves into the vinyl. Physical grooves—mountains and valleys that are literally a fingerprint of the sound. Then when you play it back, the needle traces those grooves, vibrates the membrane, creates sound again. It's all physical. The signal passes through a matrix of matter that never breaks."

I nodded. I'd never thought about it that way, but it made sense.

"But digital is different," he continued. "With a CD, the sound still hits a membrane. But instead of carving a physical groove, it gets translated into zeros and ones. The membrane moves a computer chip, which records: up is zero, down is one. The vibration becomes a code. And that code—that string of zeros and ones—can travel through circuits, through cables, through fucking air as radio waves. It escapes the physical matrix."

"It becomes information," I said.

"Exactly! And here's the thing—zero and one aren't just arbitrary symbols. They're the two fundamental states of existence. Zero is nothingness, potential, the void. One is somethingness, manifestation, the actual. And everything—EVERYTHING—is just those two states oscillating."

He pulled out a stick and started drawing in the sand.

"Look at the symbols. Zero is a circle. A hole. A womb. The feminine principle. One is a line. A phallus. The masculine principle. And if you overlay them..." He drew them overlapping. "You get phi—the golden ratio. The spiral that shows up in nature everywhere. In shells, in galaxies, in our DNA."

I stared at the drawings in the sand, my mind racing.

"It's the same pattern that governs everything," Tarquin said. "The I Ching is based on sixty-four hexagrams made of broken and unbroken lines. The Mayan calendar has the same mathematical structure. Our DNA has four base pairs that combine in patterns. It's all the same code, mate. Zero and one, oscillating."

We stayed up all night, that first night in Tulum. Talking, drawing in the sand, smoking, watching stars wheel overhead.

The next day we met two Israeli guys—Alon and Asaf—who'd been traveling overland from Chile all the way up to Mexico. They were on their last leg, almost done with a year-long journey, and you could see it in their eyes. This melancholy mixed with gratitude. Every story they told reminded them that their time on the road was ending.

We sat around a fire on the beach that night, passing joints, and the conversation kept returning to the same themes.

Why were we all here? Why were kids from Greece and England and Israel all drawn to the Mayan ruins, to trance music, to this nomadic lifestyle?

"It's because we're creating a new global culture," Alon said. "Your generation especially. You grew up analog but you're the first to go fully digital. You're the bridge."

"First Wavers," I said, remembering Tarquin's phrase.

Over the next few days, Tarquin and I rented a old VW Beetle and drove to Chichen Itza. We climbed the pyramids—back when you could still do that—and stood at the top looking out over the jungle canopy.

And sitting up there, I understood something I'd been circling around for months.

The Mayans had understood time as cyclical. History as a pendulum swinging between opposing principles. And they'd built their entire civilization around tracking those oscillations, timing their rituals to the cosmic pulse they believed emanated from the galactic core.

And now, at the end of their calendar, we were entering a new cycle. A cycle where the two principles—the zero and the one, the analog and the digital, the ancient and the modern—were finally merging.

That's what the internet was. That's what trance music was. That's what all of this was.

A fusion.

East and West. Rational and mystical. Individual and collective. Physical and digital.

Zero and one, no longer separate, but oscillating so fast they became a single thing.

The last night in Tulum, Tarquin and I did something I still can't quite believe we got away with.

We snuck into the ruins after dark—climbed over the fence, crept through the jungle paths—and sat on top of the Castle, the main pyramid, overlooking the ocean.

Tarquin had DMT.

I'd tried it once before, back in New Orleans after the breakup with Cassie. It had been overwhelming, terrifying, transcendent. I wasn't sure I was ready to do it again.

But sitting there, on top of a thousand-year-old pyramid, with the moon rising over the same ocean the Mayans had watched, it felt right.

We smoked.

And for the next fifteen minutes, reality dissolved.

I can't describe what happened. Sitting here with Akiko, I don't have the words. It wasn't visual, exactly, though there were visuals. It wasn't auditory, though there was music—some fundamental frequency underlying everything.

What I remember most is the feeling of boundaries dissolving.

Between me and Tarquin. Between us and the pyramid. Between the pyramid and the earth. Between the earth and the ocean and the stars.

We were separate beings, and also we weren't. We were individual consciousnesses, and also we were the same consciousness experiencing itself from different angles.

Like we were all just... blobs. Blobs of water with light inside. And when the boundaries between the blobs dissolved, the lights merged, and for a moment there was just one light.

One consciousness.

Experiencing itself through all these temporary forms.

Zero and one.

Oscillating.

Creating everything.

Sitting here now, trying to explain this to Akiko—watching her type, trying to capture something that maybe can't be captured—I realize what Tulum gave me.

Not answers. But a framework.

A way of understanding what was happening in the world, and what was happening to me.

The internet wasn't just a technology. It was the externalization of something that had always existed—this underlying connection between all of us. The noosphere, as Teilhard de Chardin called it. The collective consciousness that every mystical tradition had pointed toward but never had the tools to actually manifest.

And trance music wasn't just music. It was a modern ritual. A way of creating those moments of ego dissolution, of unity, of transcendence that humans have always needed but that organized religion had stopped providing.

And the journey I was on—backpacking through Central America with cameras and notebooks, documenting synchronicities, following breadcrumbs the universe seemed to leave for me—wasn't just a personal adventure.

It was participating in something larger. A global awakening. A generation of kids who'd grown up analog learning to navigate digital. Learning to merge the ancient and the modern. Learning to be citizens of the global village.

We were the First Wavers.

And what we figured out would matter for everyone who came after.

I left Tulum after a week. Tarquin headed to Palenque, following more pyramids. I went south toward Guatemala, then Costa Rica, then Peru. The journey continued.

But I carried Tulum with me. That conversation on the beach. Those drawings in the sand. That moment on top of the pyramid when all the boundaries dissolved.

Zero equals one.

One equals zero.

The pendulum swinging. The circuit closing. The two becoming one, over and over, at the speed of light, creating everything that exists.

Sitting here in Williamsburg, watching Akiko type, I can feel it oscillating. Even now. Even in this moment.

Between the experience and the telling of it. Between the story and the meaning. Between who I was then and who I'm becoming now.

Between the zero and the one.

And in that oscillation—that's where the magic lives.

That's where consciousness emerges.

That's where we become.

Akiko looks up from the keyboard.

"That's heavy," she says.

"I know."

"Do you think people will understand it?"

I shrug. "I don't know if I even understand it. But it feels true. And maybe that's enough."

She nods, saves the file, stretches.

Outside the window, Brooklyn is alive with sirens and car horns and the constant hum of the city. Millions of people, all connected through invisible networks of electricity and information.

All of us separate.

All of us the same.

Zero and one.

Oscillating.

Creating everything.

I light a cigarette and look out at the rain.

The journey continues.